Author

Facing up to Father: The pleasures and pains of a Cotswold childhood

A compelling story of growing up in the Cotswolds of the 1950s and early 60s will appeal to Cotswold residents and visitors nostalgic for descriptions of a farming life long gone. It was a time when farming life was on the verge of mechanisation, a world where the horse was still very important, where the relationships of farmers and their workforce was very different, and where the class distinctions within local communities remained very rigid.

Pre-order at Marble Hill Publishers or Amazon

A small Cotswold farm is the setting for a classic struggle of wills. Robert Worlock, eccentric and demanding, resolutely maintains the old ways, determined above all to make his son into a farmer fit to take over the family acres. His son, David, is equally determined not to be bullied into something he neither wants nor likes. His childhood becomes a battleground: can he find a way to make his father love him without denying his right to determine his own life?

Sometimes heart-rending, sometimes amusing, always elegantly written and deeply honest, this account of a young man finding himself in the most difficult of circumstances deserves to take its place among the great childhood memoirs.

Extracts from the book

“Brainwork will let you down one day, Dave, but I can teach you two things that will keep you in employment all your days.”

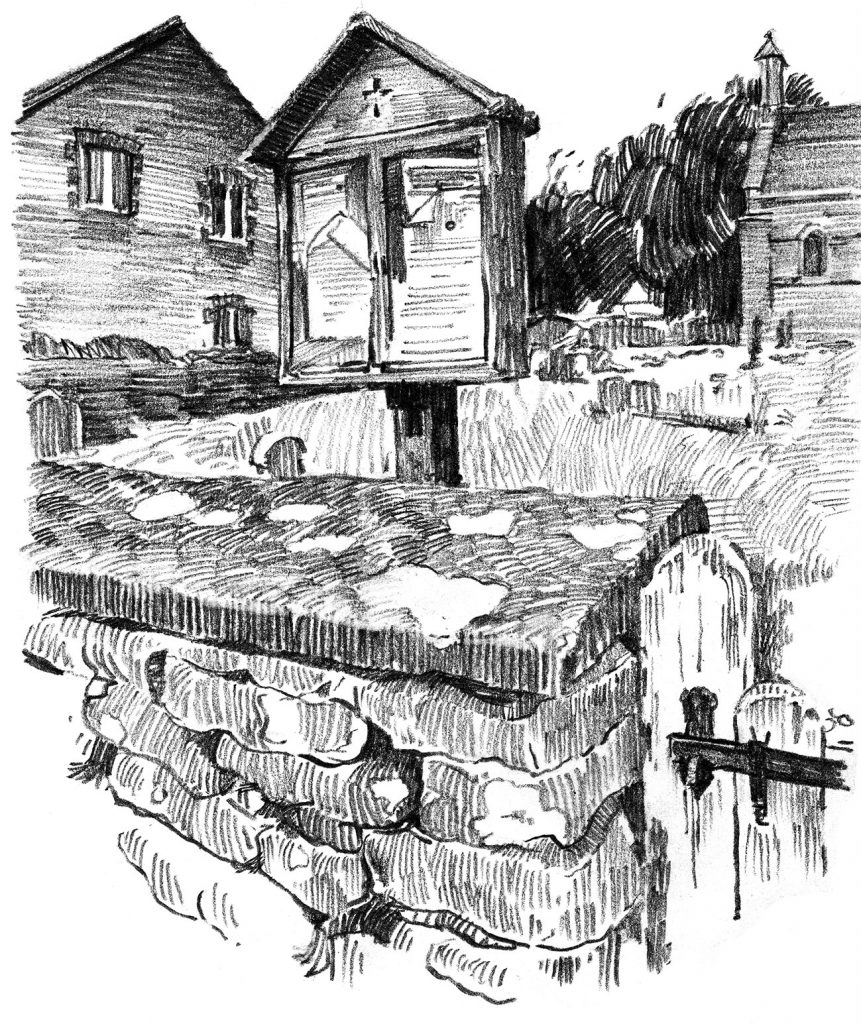

Hedge laying and drystone walling, the golden acts to which he referred, are both intensely physical activity and I was glad I was playing a good deal of rugby during those days. But they are also both thoughtfully intellectual activities. When hedge laying you must see the end result in its bushy beginning. A similar stricture applies to drystone walling. This 3D jigsaw puzzle relies on locking the stones together across the wall as well as up and down. We worked on rockeries, a ha-ha, and a flower bed shaped as a boat, but I never once handed him a stone for a slot without him pointing out that it needed another one jammed beneath it or beside it. He came out to watch me at work, sitting in the Land Rover with a flask, and then strolling over for an occasional inspection. I came to relish the cursed lips, the head shaking and at length the grudging:

“If you must do it your way, I suppose that’s half reasonable, but, mark me, you’ll have to do it all again in five years.”

Father was a man of the pre-tractor world. Twist, the old cob, was

attached to a horse hoe. This would speedily take out the weeds between the rows of mangels, leaving the hand hoes people to take out the weeds among the plants themselves. Father, at the back of the horse hoe and holding its handles and with Twist’s reins around his neck, would show us how. The demonstrator, horse and hoe readied themselves at the top of the field and then lunged violently forward: the hoe addressed the soil, and to our onlooking horror, neatly took out a line of young mangels, leaving a line of untouched weeds as evidence of the efficacy of horse hoeing over useless tractors. We knew better than to laugh.

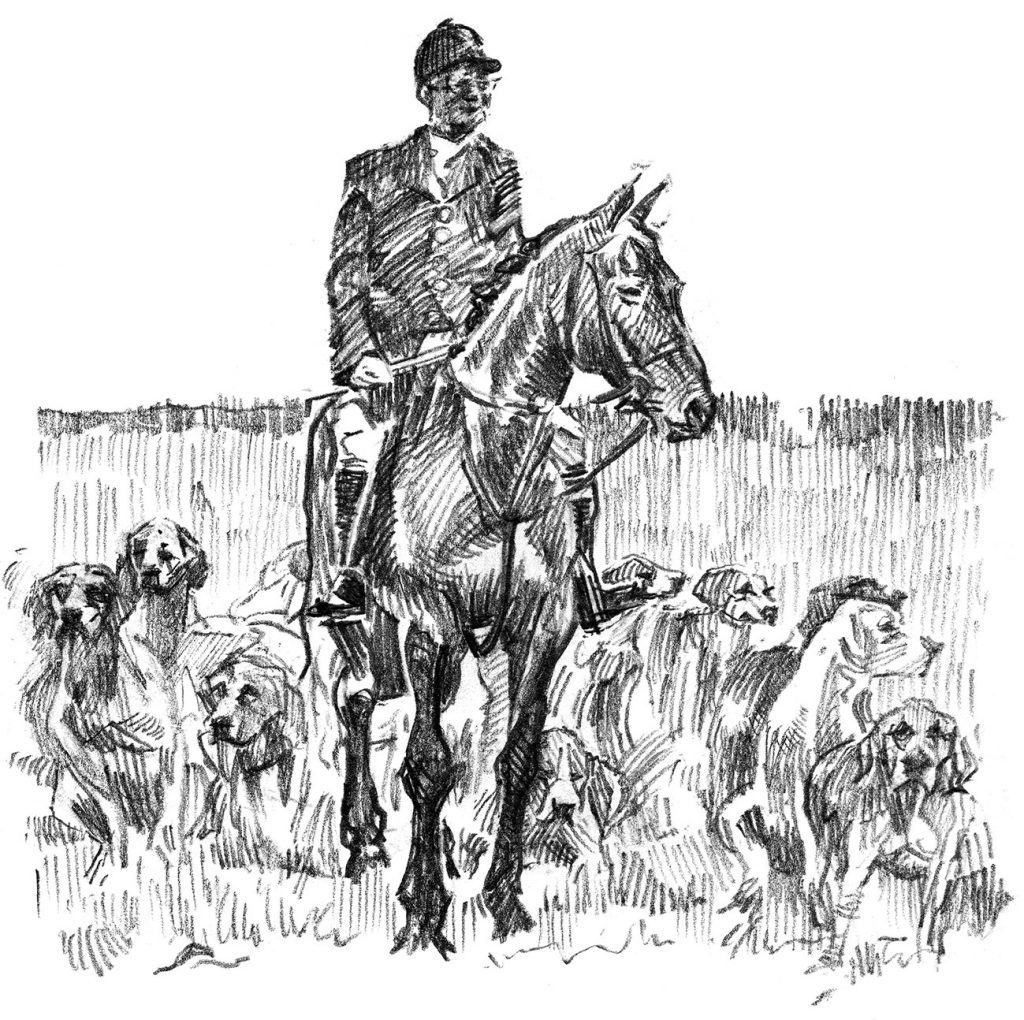

So on that rare day, when I was ten, and the Beaufort Hunt

actually drew the woods at Westerleigh, I was unready for revelations. A fox was hunted as far as our small coppice at the bottom of Sixteen Acres.

Seeing the direction of travel, Father came racing down Nibley Lane as if he was bringing the news from Aix to Ghent, and he shouted at me:

“Stand by the Sixteen Acres gate until His Grace comes by, then open up and let him through.”

At last I was to meet His Grace and I did not have long to wait. First came a few stray hands, then a perspiring kennel huntsman in the green jacket denoting those hunt servants involved in hunting hounds. After these altar boys and archimandrites, came the Duke of Beaufort, Master of Foxhounds, a middle-aged man with steel-rimmed spectacles and a ‘never surprised’ expression.

The whipper-in said, “We lost him across the railway line, Your Grace,” and my shock was so complete that for a moment I forgot to open the gate. The Duke and His Grace were one and the same person. We used ‘Your Grace’ to designate him as a living god. It was all a bit reminiscent of the Holy Trinity. Suddenly, for some reason, I felt a lot clearer about matters theological and and cosmological.

And I did open the gate. As I did, the great man leant down in the saddle and said, “Are you Robert Worlock’s son?”